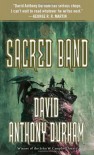

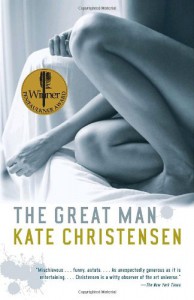

The Great Man - Kate Christensen

I’m quite grateful to the former colleague who left this book in my office despite my protestations that I don’t have the time to read this as well and that I’m not interested and that I already have several dozen books at home waiting to be read (and reviewed) anyway. I can honestly say that I would never have picked up The Great Man myself. The book cover and synopsis looked totally unappealing to me. Since she always reads everything I lend her I felt compelled to at least take this book home with me and add it to the stack of books she’s already forced on my in the previous months. And the very next day I decided to read the first few pages so I would be justified to say “not my cuppa” and put it aside – at least I would have tried. Interestingly, I kept reading.

The story-telling is intriguing, the themes and topics pile up and you get the feeling that you could write academic papers on the treatment of this and that aspect in the novel along the way. It gets you thinking about all kinds of existential questions.

The mystery or big secret (a bet, really) was hinted at early on but took completely second place to my reading and enjoyment of the novel. I just wanted to read on and didn’t know why. I didn’t identify with any of the characters, didn’t even feel particularly sympathetic towards them, I wasn’t interested in seeing what would happen to them or what would be revealed about their past and intricacies. They sort of crept up on me. I didn’t get actively invested in them – or I never noticed when I did. When one of the characters died (which was to be expected) I did feel bittersweet about it even though she was the character I liked the least, a cantankerous, bitter, old women – ghastly, lonely. Brilliantly portrayed by Christensen!

The great man of the title is painter Oscar who we are supposed to learn more about through the narratives of the women in his life as told to two interviewers researching for their books. Oscar is not the hero of this book. He’s not even a subject. He’s an object and in light of what is being revealed about his character, his treatment of people and art, his very own insecurities, this objectification is excellently executed. Oscar wasn’t special or especially interesting, yet he seemed to be a great influence or focal points in the lives of the women portrayed here. It’s a turning of the tables. In a way, a reversal in the question of victim and culprit. Heroines are characterised as “strong women” more often than not these days, the women in The Great Man come out stronger than most and you would never have suspected it on a glance. It’s a bit like “The First Wives Club,” only that the women here never have to take revenge as they don’t see themselves as the victims of a man. These women do not glorify the supposedly “great man” in their lives, they don’t even seem to respect him much. They are quite independent, contrary to expectations.

The development of relationships over time and space, the power of the retrospective gaze, recollections, memory, nostalgia (or lack thereof) are some topics. Art, artistic perception and appreciation, criticism and interpretation are intertwined with excursions discourses on language, sexuality, society, and relations. There’s the question of the power of love versus the struggle of love=power, nicely encapsulated in a dialogue between Ruby (older daughter of Oscar and Teddy) and Ralph (one of the biographers):

”Must be wonderful,” said Ralph, “to be the daughter of two people so in love.”

“Not especially.”

“That’s not what I expected you to say.”

“My grand theory about my parents is this. My mother was the lover and my father the beloved. From watching them, I drew the conclusion that it’s best to be the lover, the one who adores and pursues. Love is tangentially about power, and the beloved has less power than the lover, all appearances to the contrary. In other words, my mother had more power over my father than he did over her. That’s always how it works, no matter how it may appear on the surface.” (page 67)

The two biographers (interviewers), who compete with each other without knowing and who unwittingly become instruments of the women’s controlling of the narrative, only play a marginal role, which makes them even more interesting. The women are only supposed to provide details for the portrayal of the great man, Oscar, but instead of becoming minor objects in the story of the biographies’ subject, they become puppet masters instead.

Ageing and old age and the differences and similarities in the approaches and reactions of Maxine, Teddy, Lila, and Abigail present another focal point of the novel. Here’s an observation from Maxine’s point of view:

One thing about getting old was that your openness to new people shrank through the years from a naïve embrace to a narrow squint. By the time you hit old age, you barely had the ability to be civil for one minute to any stranger, let alone get through a whole evening of “interesting” conversation. (page 96)

Maxine’s bitterness any cynicism and disappointment with the whole world and people at large is suffocating and stifling and oddly entertaining, at least for me. I felt sorry for her but also was very amused by her curmudgeonly rants.

The real problem was that the human race was so disappointing. Why had she expected it to be otherwise? As a young woman, Maxine had tended to leap with open arms, like a wet-eyed, splayed-out nincompoop, toward everyone she met, but she had quickly encountered enough snideness, selfishness, neediness, cruelty, rejection, and indifference to enable her to gradually develop the social crankiness that had by now become thick and insuperable as an old toenail. (pages 96-97)

There are also excursions into politics, culture and its representation, in particular African-American culture “mumbo jumbo” as vocalised by the secondary character of Paula Jabar.

As I’m writing this, I realise that the least sympathetic character of them all, Maxine, might indeed be my favourite. She’s cranky, she’s mean, but she’s also lonely and feels left behind and too far removed from this world. We are led to believe that there was bitter sibling rivalry between her and her brother Oscar, but at the very least, he was someone from her own youth, someone she felt connected with. Now that he’s gone, she feels her own displacement even more harshly. I was quite moved by the bit of narrative from her POV after she feels out-of-place at an artsy-fartsy party, where she was expected to mingle and make polite conversation with other artists, buyers, and agents:

In the old days, the painters at such a party could well have been pissing in corners, drunk as bums, arguing so hard they spat at one another. She missed her brother with a sharp pain in her chest; she thought for a moment that she was having a heart attack until she realised that it was just nostalgia. (page 116)

As I said, the book is full with all kinds of themes to ponder. There’s a lot about self-reflection, taking risks in life, suffering, rejection, and failure. In tandem with the topic of ageing, there’s also quite a bit of reflection on death and dying, a topic I usually give a wide berth (unless it’s in genre fiction – there it’s awesome in al its forms! :o)): death is presented as a freedom from need, but the terrifying dimension, described as a suspension in nothingness, is also acknowledged. Well, there’s a lot to think about, but not to get dragged down by. The tone of the novel is never heavy, never depressing.

There was one aspect in the narrative that I might not have fully understood. I put it down to comic relief (I found it funny) and did not overanalyse. However, if anyone who’s read the book and stumbles about this here review would care to enlighten me, I’d be grateful: What’s Harry’s obsession with that morphine-addicted poet Greta Church (the one he wrote his first biography about) really about? Is it mockery of literary analysis and criticism? Is it about taking oneself and one’s subject matter to seriously? Is it meant to show that one’s worth as an artist does not necessarily increase after death despite a single fan’s best efforts? I mostly understood it as a device to show the three (or four) women’s similarities, because they all had similar reactions to the snippets of poetry Harry quoted at them. “That reminds me of a children’s nonsense rhyme.” (page 147)

Well, this has already gone on longer than expected so I’ll end here. The Great Man was intriguing and beguiling reading for me, something completely different from my usual literary diet.